Liver abscesses are pus-filled cavities within the liver that arise when infection overwhelms hepatic tissue. They are a serious medical condition that requires prompt diagnosis and treatment. Abscesses can result from a variety of causes, including bacterial entry through the biliary tract, the bloodstream, or direct extension from neighboring structures.

They also arise from trauma, surgery, or, less commonly, parasitic or fungal infections. Understanding the causes and risk factors helps clinicians identify patients who need rapid evaluation and intervention, and it helps patients recognize warning signs that warrant urgent care.

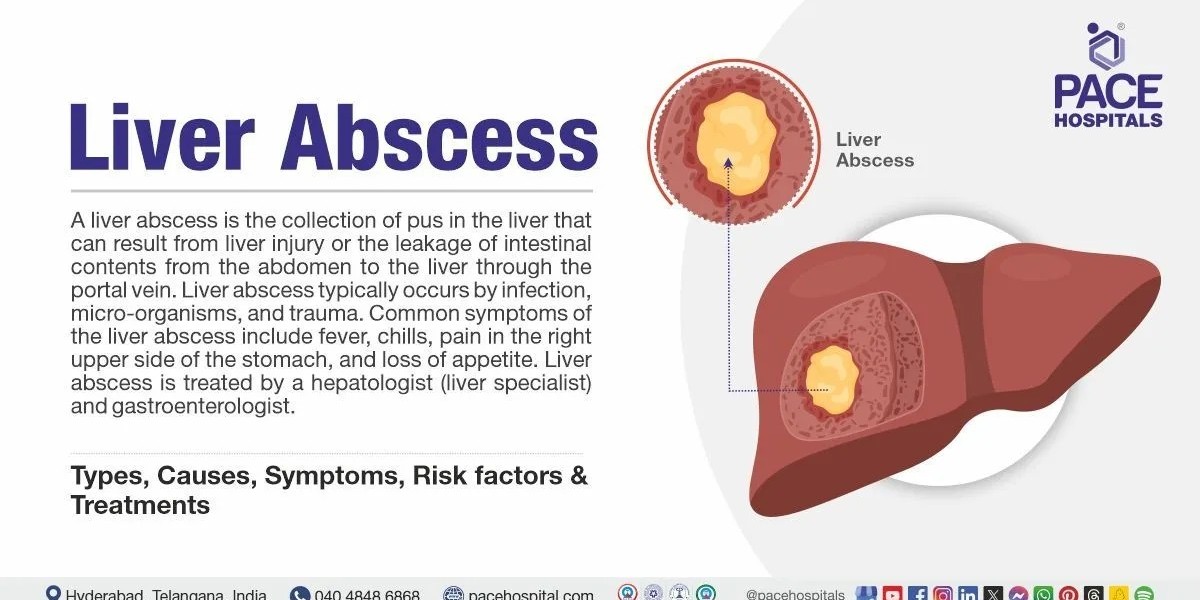

What is a liver abscess?

A liver abscess is a localized collection of pus within the liver due to infection. Abscesses can be solitary or multiple and can form in different liver segments. They may present with fever, right upper-quadrant abdominal pain, tender liver edge, nausea, vomiting, and malaise. Some patients, especially the elderly or those with weakened immune systems, may have subtle symptoms or atypical presentations. Laboratory tests often show elevated white blood cell counts and inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein. Imaging usually ultrasound or CT scan confirms the diagnosis and helps guide drainage if needed.

Major routes of infection

- Pyogenic (bacterial) liver abscesses

- Most common type in developed countries.

Pathways: Bacteria reach the liver via the portal vein from abdominal infections (diverticulitis, appendicitis, diverticulitis), via the hepatic artery from a distant infection, or from biliary tract infections such as cholangitis or cholecystitis.

Common organisms: Escherichia coli, Klebsiella species, Streptococcus species, and anaerobes. Polymicrobial infections are not unusual in biliary-origin abscesses.

Risk factors: Age, diabetes, liver disease, biliary obstruction, recent abdominal surgery or instrumentation, and immunosuppression.

Amoebic liver abscesses

Caused by Entamoeba histolytica, more prevalent in parts of the world with poor sanitation and limited access to clean water.

Route: Ingestion of contaminated food or water; the parasite seeds the liver via the portal circulation.

Presentation: Fever, right upper-quadrant pain, and a tender liver; often no localized abdominal source of infection.

Treatment: Antiparasitic therapy (e.g., metronidazole) often followed by luminal agents; drainage is rarely required unless complications arise.

Fungal and parasitic liver abscesses

Fungal abscesses are less common but can occur in severely immunocompromised patients (e.g., those with uncontrolled diabetes, chemotherapy, or organ transplantation).

Parasitic abscesses can result from organisms such as Echinococcus or other parasites in endemic regions.

Hydatid cyst rupture and secondary infection

Echinococcal disease can form cysts in the liver, and secondary bacterial infection of a cyst can produce an abscess-like cavity.

Direct extension and trauma

Abscesses may form after penetrating or blunt abdominal trauma or after surgical procedures that introduce bacteria into hepatic tissue.

Post-procedural and post-surgical abscesses

Infections can occur after hepatic procedures, biliary interventions, or abdominal surgeries, especially when sterile technique is compromised or when drains remain in place.

Host factors that raise risk

Immune status: Patients with diabetes, alcoholism, malnutrition, HIV infection, or those receiving immunosuppressive therapy have higher susceptibility.

Liver disease: Cirrhosis, hepatic steatosis, and other chronic liver conditions can predispose to infection and alter local hepatic defense mechanisms.

Biliary tract disease: Obstruction, stones, or cholangitis increase the risk of bacterial entry into liver tissue.

Vascular and systemic factors: Sepsis, bacteremia, and poor perfusion can facilitate infection reaching hepatic tissue.

Age and comorbidity: Older adults and those with multiple comorbidities often present with atypical symptoms and higher complication rates.

Clinical presentation and diagnosis

Symptoms: Fever, chills, right upper-quadrant or epigastric pain, tender liver, nausea, vomiting, and malaise. Some patients experience weight loss or jaundice, depending on the abscess location and size.

Physical exam: Right upper-quadrant tenderness, hepatomegaly, and sometimes signs of systemic infection.

Laboratory findings: Leukocytosis with neutrophilia; elevated inflammatory markers such as CRP and ESR. Liver function tests may show cholestasis or hepatocellular injury in larger abscesses.

Imaging: Ultrasound is frequently the initial modality; CT scan provides detailed anatomy and is highly useful for planning drainage. MRI can be helpful in complex cases.

Microbiology: Blood cultures and abscess aspirates guide antibiotic therapy and reveal causative organisms. In amoebic cases, serology and stool tests help distinguish etiologies.

Management strategies

Antimicrobial therapy

Empiric antibiotics: Broad-spectrum coverage is typically started promptly, tailored later based on culture results and local resistance patterns. Regimens often include agents active against gram-negative and anaerobic organisms.

Duration: Courses vary with the source and response, but total therapy commonly extends for several weeks, sometimes with a transition from IV to oral antibiotics.

Targeted therapy: When cultures identify a specific organism, therapy is narrowed accordingly to limit resistance and adverse effects.

Drainage and source control

Percutaneous aspiration or catheter drainage under imaging guidance is common for sizable abscesses, particularly if they fail to respond to antibiotics or are at risk of rupture.

Surgical intervention may be necessary for ruptured abscesses, complex multi-loculated collections, or when concurrent intra-abdominal pathology requires repair.

Supportive care

Hydration, analgesia, and monitoring in a hospital setting are standard.

Management of underlying conditions (diabetes control, biliary drainage if needed) improves outcomes and lowers recurrence risk.

Special considerations

Amoebic liver abscesses require antiparasitic therapy in addition to antibiotics if bacterial superinfection is suspected.

Immunocompromised patients may require broader diagnostic workups to identify unusual pathogens.

The role of the broader parasite-control supply chain

Medicines and diagnostics: Effective management relies on reliable supply chains for antibiotics, antiparasitic agents, imaging modalities, and laboratory tests.

Meant to be familiar in supply discussions are terms like mebendazole wholesale or other distributor keywords. While mebendazole is used for certain helminth infections, it is not a frontline therapy for bacterial, amoebic, or fungal liver abscesses. Its mention in wholesale or distribution contexts reflects logistics and procurement considerations in parasite control programs rather than direct clinical management of liver abscesses.

Quality and access: Ensuring consistent availability of essential medicines reduces delays in diagnosis and treatment, which is critical for favorable outcomes in liver abscess patients.

Prevention and prognosis

Prevention hinges on addressing underlying risk factors: good diabetes management, safe water and sanitation in areas prone to amoebic infections, prompt treatment of biliary or intra-abdominal infections, and vaccination where applicable.

Prognosis improves with early detection, appropriate antimicrobial therapy, and timely drainage when indicated. Complications such as rupture, sepsis, or portal vein thrombosis worsen outcomes, but many patients recover fully with comprehensive care.

Follow-up: After treatment, follow-up imaging may be required to ensure resolution, especially for large or complex abscesses. Monitoring for recurrence or ongoing liver disease is important in patients with predisposing conditions.

Public health and education implications

Awareness: Educating clinicians and the public about the signs and risk factors for liver abscesses improves early presentation to care.

Access to care: Equitable access to imaging, laboratory testing, and effective antimicrobials is essential, particularly in rural or resource-limited settings.

Research gaps: Understanding the local epidemiology of liver abscesses, antibiotic resistance patterns, and optimal drainage strategies continues to improve patient outcomes.

Supply chain transparency: In discussions about parasite control or broader public health programs, the inclusion of distributor terminology such as mebendazole wholesale helps illustrate the interconnectedness of clinical care and supply logistics, even though such products are not primary treatments for liver abscesses.

Key takeaways

Liver abscesses stem from diverse causes, including bacterial infections, amoebic infections, fungal infections, direct extension, and post-procedural complications. Underlying health conditions, biliary disease, and immunosuppression heighten risk.

Prompt recognition, broad-spectrum initial therapy, and timely drainage when needed are central to favorable outcomes.

Managing comorbidities, ensuring access to diagnostics and antimicrobials, and understanding the role of supply chains in parasite control all contribute to effective public health responses.

When discussing supply chains and pharmacology, terms like mebendazole wholesale may appear, but they are part of broader logistics rather than direct clinical treatment for liver abscesses.

If you’re writing for education, policy, or clinical guidance, this overview emphasizes the importance of rapid assessment, source control, and comprehensive care, while acknowledging the broader context of drug distribution networks in disease management.